What is a Dog or Cat Hookworm?

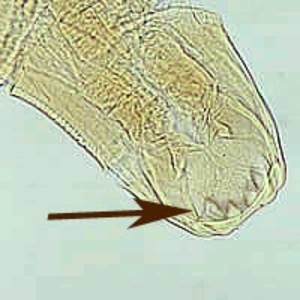

Hookworms are parasites that live in the small intestine of infected animals. Although quite small at only � to ? of an inch long, hookworms are potentially very dangerous, especially to puppies and kittens.

They attach to the intestinal walls to feed on blood, and their vampire-like appetite can quickly cause severe anemia, or even death in young animals.

There are a a number of species of hookworm:

- Ancylostoma caninum is the most common and causes the worst disease in dogs, but doesn't affect cats at all.

- Ancylostoma tubaeforme is the most common hookworm in cats, but not affect dogs.

- Ancylostoma brazilense and Uncinaria stenocephalaoccur are found in both cats and dog. While they are common in dogs, they are quite rare in cats.

|

Signs of hookworms

|

Once larvae have emerged, there are a number of ways in which they can

infect animals, including:

|

In dogs, an adult A. caninum worm can remove up to 0.8mL of blood each day! If a dog were carrying 100 parasites this would add up to 80mL a day. In a small pup, this would mean a significant proportion of its blood volume being removed in just a few days. Heavily-infected pups can lose 25 per cent of their red blood cells a day.

A. caninum prefers warmer climates in the more southern states, while A. brazilense tends to be more common in tropical regions. Uncinaria stenocephala prefers cooler regions and is also known as the Northern Hookworm. It removes far less blood than A. caninum, just 0.0003mL per worm per day.

Light hookworm infestations in cats tend to show no signs. A. tubaeforme is the major blood-sucking parasite in cats, with the other two being less insignificant as they do not remove as much blood. Many cats will spontaneously eliminate these parasites from their gut.

In both cats and dogs, adult hookworms mate in the intestines. Females lay eggs which are passed out in the feces about 14 to 20 days after infection. The eggs hatch within three days and reach the infective stage in about a week. This is why it is important to pick up dog feces as soon as possible after the dog has deposited it.

Sometimes hookworm larvae halt their migration and lie dormant for long periods in tissues such as the gut wall or abdominal lining. They can be stimulated to continue their migration by a developing fetus; by the removal of adult worms from the intestine and by milk production. While canine pups are suckling, the mother can excrete larvae in milk for up to 20 days. This does not occur in cats.

As the worms graze their way through the intestine, feeding on blood, they leave a bloody trail. Some pups require a blood transfusion to survive. Iron supplements may also be required in severe cases, along with a high-protein diet to allow the dog to replace the lost blood cells.

|

Hookworm infection

|

Signs of hookworm infection include:

|

Migrating hookworm larvae entering the skin cause itchy tracts under the skin. These are most common in areas where the animal comes into contact with the ground, including feet, chest, belly, ankles and forelegs.

Dogs in unhygienic, fecally-contaminated kennels often develop painful cracks and sores around the edges of their footpads The pads themselves become spongy from these migrating larvae. The tracts are often visible under the skin where the larvae are migrating, known as hookworm pedal dermatitis, which can be very itchy and in severe cases, causing deformed nails. Breeding kennels where dogs are kept on soil or dirt also have a high prevalence of infection. Elevating kennels off the ground can dramatically reduce the incidence of hookworm pedal dermatitis.

Hookworms can also penetrate the skin and migrate in humans, causing red, swollen tracts in the skin which are intensely itchy. This condition is referred to as cutaneous larva migrans.

Treating pets for hookworms is important, not only for the health of the pet but also the health of your family. There are several ingredients on the market which are effective in killing hookworms, including pyrantel, febantel and levamisole. Many of these also treat other kinds of worms. Your veterinarian can advise you on the most appropriate choice for your pet.

|

Anti-hookworm treatments

|

Pet Shed's most popular solutions for ridding your pet of

hookworms

|

Current recommendations for puppies for intestinal worm treatment state that they should be treated at two, four, six, eight, ten and 12 weeks of age, then monthly until they are three months old, then at least every three months for the rest of their lives. Pregnant dogs should be treated from at least day 42 of pregnancy, and every two weeks throughout the time that the pups are suckling.

Current intestinal worm treatment recommendations for kittens state that they should be treated at six, eight, ten and12 weeks of age, then monthly until three months old, then at least every three months throughout life. Pregnant cats should be treated at least ten days before kittening and then every two weeks during the time that the kittens are suckling.

|

References

|

| Kassai T, (1998). Veterinary Helminthology. Butterworth Heinemann, UK. Payne P.A., Carter G.R. Internal Parasites of Dogs and Cats. In: A Concise Guide to Infectious and Parasitic Disease of Dogs and Cats. International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca, NY. www.ivis.org Tilley, L.P., Smith, F.W.K. The Five Minute Veterinary Consult Canine and Feline. Second Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 2000. |